Katie Ashford is an English teacher in a secondary school in London. These are her individual views.

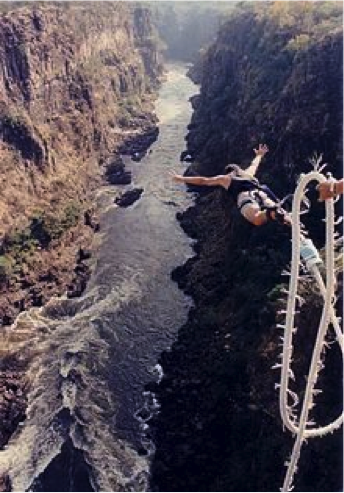

Teach First: the teacher training equivalent of a bungee jump; an exhilarating, frightening, all-or-nothing experience that is not for the faint hearted. The six week training period, known as ‘Summer Institute’ is like standing on the edge of a great precipice, fear and trepidation consuming your every nerve and sinew. As you look out across the cavernous maw before you, you stare blindly ahead, desperately hoping you will make it back alive. When the first day of school arrives in September and you can finally take the leap you have been worried about all summer, you are suddenly thrown into the air and are whipped about in the breeze, flailing around like a ragdoll, unable to breath.

My two years are drawing to their close. I am now hanging upside down, dishevelled, delighted that I survived and determined to keep going, to do it again, but this time, to do it even better. I am by no means a great teacher. I’ve spent the last year realising exactly what I don’t know, which is a strangely motivating force. I have learnt far more than I ever thought possible, and below are just some of the things that I have taken from this experience. They outline what has shaped my view of teaching and of the education system, but constitute a mere drop in the ocean of what there is to be learned about the profession.

Here are a few things I have learnt on Teach First:

School leadership matters more than anything else

All kids need structures and routines. Kids from challenging backgrounds need this even more so because they often do not get it at home. So much of this comes down to school ethos; this must be set by SLT. Individual teachers can try to implement routines in their own classroom, but it will be extremely difficult without school level structures in place to support them. Great leaders make teachers’ jobs easier by creating an ethos of hard work, respect and success; weak leaders don’t.

Kids are brilliant

Being a teacher is a bit like this:

You get questions about your personal life on a daily basis and brutal honesty about the quality of your teaching. You are regularly made aware of a child’s immediate need to break wind and can grow tired of being asked for a ruler fourteen times in a row. Sometimes, you get kids coming back to see you at lunchtime to ask you burning questions about Shakespeare, or to say sorry for letting you down. You will hear more poorly thought out lies and more heartfelt honesty than you ever imagined. You will be angry, and you will be proud. You will get to know some genuinely inspiring young people and will hope that you contribute in some small way towards their futures.

It’s not an easy job, but that doesn’t really matter. Kids are brilliant; they make me laugh, they make me think, and they make all the hard work totally worth it. Call me cheesy if you must, but it’s true.

Poverty affects learning

Before I started teaching, I was aware that children from poorer backgrounds did not generally do as well as those from better-off backgrounds. 3 years at university taught me that: hardly anyone I knew at university went to a state school, never mind came from a deprived area.

The thing is, in the classroom, I could see the damaging effects of poverty everywhere I turned: kids wearing the same filthy clothes for days on end, kids whose parents do not own a single book, kids who have never left the local area, kids who don’t know who Thatcher was. The effects of poverty are not merely financial. There is a dearth of cultural wealth for many of these children too. They don’t visit museums, they don’t watch documentaries, and they don’t get read to. As I got to know the kids I taught, the evidence of this poverty became abundantly clear, and it made me uncomfortable. It holds them back from succeeding in ways that I simply could not fathom until I had stood in front of them, in a classroom, and taught them something.

What you teach matters.

Often, we are told that no school is better than it’s teachers. To a certain extent, this is true. You need great people in the classroom who can inspire and motivate their students. These people need to be able to deliver lessons in the most effective way possible so that the students learn as much as they can in the short time they have at school. But (and this is a big ‘but’) this depends dramatically on what we teach. When I first started out, I taught what I knew best and what I thought the kids would like. Turns out, this isn’t the best way to plan a scheme of work. We should be teaching well-sequenced, sensible curricula that challenge young people and give them the knowledge and skills they will need to be well-informed members of society.

It was precisely because of the poverty I saw that I came to such a conclusion; some children have very narrow horizons because of the world they are growing up in. As an English teacher, I felt it my duty to broaden their horizons by teaching them about worlds they knew little or nothing of, by transporting them to times and places they have never heard of, and hopefully inspiring them to go away and learn more.

I quickly realised that my strategy of using soap operas and magazines simply would not cut the mustard. Even if I taught these texts in the most exciting way possible, the kids’ understanding and appreciation of the wider world would not improve much. And so I swapped magazines for Conan Doyle; I haven’t looked back since.

The education system needs to get better

There are many great things about the education system in the UK, but there are also many things that still need to be addressed. The gap between our disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils is an urgent issue, one that thousands of dedicated teachers are working towards solving every day in their classrooms across the country. I hope that over the next few years I can begin to count myself as one of them.

Although I may not have all the answers just yet, I am sure that the system needs to get better. Teach First has helped me to figure out why this is the case; I have an intimate, visceral understanding of the challenges our most disadvantaged pupils face, and am looking forward to seeing how we move towards changing this in the future. Teach First has given me the courage to keep going, the conviction to challenge the status quo, and the hope that it will get better.

Subscribe to Edapt today from as little as £8.37 per month to get access to high quality edu-legal support services to protect you in your teaching and education career.

SubscribeLatest Support Articles

Our support articles provide up to date advice on a wide range of topics including pay and conditions, maternity and paternity, dealing with allegations and staying safe online.