Katie Ashford is an English teacher in a secondary school in the Midlands. These are her individual views.

I remember the first few times I was observed as a trainee. Most things in my training year were utterly horrendous, and observations were no exception. But what I remember perhaps even more than the lessons themselves was the bizarre thought processes I seemed to go through when planning for them. I was always a complete bag of nerves, and spent more time worrying about what might go wrong than actually planning my lesson. “What if a bee flies in?!” “What if the fire alarm goes off?!” “What if I fall over or the projector isn’t working?”

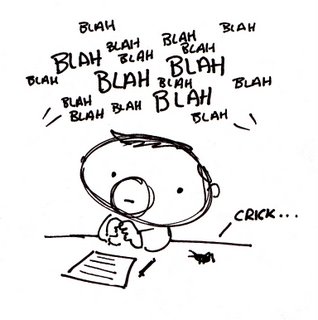

But my biggest concern during those early days was how to make sure I did not spend too much time talking. It had been drilled into me by those who trained me, and by other teachers, and by every single book about teaching I had ever read, that teacher talk was the worst possible thing I could do. For this reason, I had it in my head that if I spent more than two minutes explaining something, an enormous hellhole would open up at my feet and I would be doomed for eternity.

It’s because the idea of ‘teacher talk’ conjures up images of ancient, dusty old teachers in caps and gowns, standing in front of blackboards and forcing children to recite Latin verb endings until they can do them in their sleep. It sounds like something from a Dickens novel: unpleasant, dull and cruel. No 21st Century teacher wants to be that guy. I certainly didn’t.

But our fear of teacher talk doesn’t stop at the end of our training year. Even the most experienced teachers would hesitate before talking for too long during a lesson observation or when an Ofsted inspector pops by. Even if there is a tiny part of us that secretly thinks that teacher talk isn’t as bad as we make out, we daren’t risk it when the clipboard crew arrives. Teacher Talk is perceived to be observation suicide: that’s teaching rule number 1.

And so, with the aim of improving our teaching in mind, a large proportion of CPD time is dedicated to thinking of innovative ways to prevent teachers from talking as much as possible. We ask our teachers to ‘encourage pupils to take ownership of their learning’ and ‘hand over the work to them’; we promote the use of ‘independence strategies’ such as ‘Brain, Book, Buddy, Boss’; we invite teachers to take a step back from the whiteboard, and to allow the pupils to discover the answer themselves. This, it is often argued, is not only a more engaging experience for pupils, but also a far more effective way for them to learn. To sit and listen to a teacher tell you things is a passive activity; to spend time working through and discovering the answer yourself requires the mind to be switched on and active, therefore enhancing and accelerating learning.

Brain, Book, Buddy, Boss

Aside from being boring and outdated, teacher talk is derided for not helping to create ‘independent learners’. We worry that if we spend too much time telling our pupils the answers that they will never learn how to figure things out for themselves in the future. However, as Daisy Christodoulou argues in her excellent, recently published book, ‘teacher instruction is vitally necessary to become an independent learner’.

And I agree.

Of the many strategies that have been devised to aid and develop independent learning skills, the ‘Brain, Book, Buddy, Boss’ approach appears to be one of the most common. ‘Brain, Book, Buddy, Boss’ encourages pupils to look to three other resources before they ask the teacher a question. Again, this seems like a reasonable enough suggestion. Of course we want to encourage our pupils to think for themselves. However, despite having the noble aim of independence in mind, the strategy fails to appreciate some of the problems that may arise from it.

For example, a pupil may be flummoxed when trying to understand what the word ‘dire’ means in the sentence: ‘The concert was dire’. What are they to do in this situation? According to this strategy, they ought first to think more carefully about it, then to check their book and see if they might find the answer there. If these pursuits do not prove fruitful, pupils are then encouraged to ask a ‘buddy’ for help. Again, this is a reasonable enough suggestion. The child sitting next to them may have understood the meaning of the line instantly and might be able to explain it clearly to their classmate.

But this approach may give rise to a number of misconceptions. First, the pupil might simply assume that the word ‘dire’ means ‘great’, and therefore infer that the concert was fantastic. Secondly, the pupil might look the word up in the dictionary and see the following: “(adj) extremely serious.” Although this definition is correct in some contexts, it is not in others, and more importantly, it has not helped the child to understand the meaning of the sentence he is struggling to understand. Unfortunately, using a dictionary to learn the meaning of words requires a lot of prior knowledge of other words, which our pupils often lack.

Thirdly, the pupil might decide to turn to their partner and ask them for some help. Let’s say the other child has already formed a misconception about the word and tells them it means ‘something to do with dinosaurs!’- Another unhelpful misconception.

In such a situation, if a child were stuck on something like this, I would actually prefer them to put their hand up and ask me the question, for two reasons. First, neither they nor their classmates are experts: the teacher is. Teachers have far more knowledge than their pupils, and are better suited to explain concepts and tease out misconceptions than another child, or the child herself. Secondly, there is an enormous opportunity cost involved when allowing pupils to work things out for themselves. It is often far more efficient to simply tell pupils the answer to such problems. Additionally, time spent thinking about the wrong things is unhelpful when it comes to helping pupils remember things in the longer term. As cognitive scientist Daniel T. Willingham says ‘memory is the residue of thought’ meaning that we remember what we spend our time thinking about. Therefore, if we spend a longer time thinking about an incorrect definition of a word than the correct one, we are actually more likely to remember the wrong definition than the right one!

Bad vs. good teacher talk

Of course, I am not advocating a return to the dull Victorian classroom of schooldays past. There is no doubt that lecturing a class of thirteen year olds for an hour is an ineffective pedagogical method. However, we ought not to disregard teacher talk completely. It certainly has its place, but it is incredibly difficult to get right. Siegfried Engelmann’s theory of Direct Instruction has offered enormous insight into what makes effective teacher talk. I discovered his work during my first year of teaching after enlightening conversations with other teachers. Although I still have much to learn about Direct Instruction, it has already had a huge impact on my teaching, improving it in many ways.

Edapt provides individual support and protection for teachers in allegations and employment issues.

Subscribe to Edapt today from as little as £8.37 per month to get access to high quality edu-legal support services to protect you in your teaching and education career.

SubscribeLatest Support Articles

Our support articles provide up to date advice on a wide range of topics including pay and conditions, maternity and paternity, dealing with allegations and staying safe online.